Posted on July 26 , 2016

Different Arts in One World

Hidemichi Tanaka

Professor Emeritus of Tohoku University

Former vice President of CIHA

1.On Multiculturalism

We, Easterners, recognize that Western scholars are now negative against Eurocentrism and insist rather now on Multiculturalism, which respects and esteems even minor cultures in the World. It began with inner ethnic problems in Western countries, but extended to the mutual cultural problems in the world against Eurocentrism(1).

We agree with their attitudes, but now, frankly speaking, we have confronted the apathy of historians and critics, because every culture of non-Western countries could not be easily studied and evaluated. Consequently, among non-Westerners, apathy has fallen into a stagnant state of communication, and the frustrations have arisen about these phenomena.

The apathy of the studies for foreign cultures based on the theory of Multiculturalism now spreading in the world (2). Unfortunately there is no mutual discussion among them. But to revive this stagnant condition, we must reexamine the ancient theories of Culture or Civilizations established by Western scholars. They think that these theories were derived from Eurocentrism.

As a representative philosopher of Eurocentrism, Friedrich Hegel(1770-1831) insisted on the idea of the History of Art. He explained it with the three stages: first is a “primitive” stage, like Egyptian or Oriental Art; and the second is a Classic period like Greek Art, before the 4th century B.C., which was represented with the balance of forms and spirits; and the third stage is Romantic Art, like the European-Christian Art, which lost the balance of spirits, and, at the same time, was spiritualized. We know also that Hegel’s Philosophy of History explains the stages of the Oriental world in the first stage, so to speak, Asiatic Autocracy. That idea of the progressive stages of history could be adapted to the History of Art. Now, do the Western historians criticize well this Hegelian concept? (3)

After Hegelism, European scholars reflected his idea, and in the 20th century, the idea of relative assessment of each culture dominated among Western Historians.

For example, according to Arnold J. Toynbee, famous English historian, there are twenty-one civilizations in World History, while Oswald Spengler insisted on eight civilizations. MacNeer named nine civilizations in History, and Bagbee covered nine civilizations, distinguishing Chinese and Japanese each as one, counting eleven, if the Orthodox Church and Catholic Church are separated. For them a Culture belongs to the Civilization. Recently Samuel Huntington observed eight: Western European, Islamic, Indian, Chinese, Japanese, Slavic, Latin American, and African. Otherwise, Melko, insists that in World History there were twelve principal civilizations and, among these, seven no longer exist: Egyptian, Cretan, Ancient Grecian and Roman, Byzantine, Central American, Andean. He declares that five civilizations exist: West European, Islamic, Chinese, Japanese, Indian and African.(4)

Distinguishing each civilization, we could discuss the cultural and artistic problems. If we accept the basic concepts of the Civilization, we could discuss about their culture and arts. Even when the language, culture, and religion are different, we could discuss about the Art. In fact the cultural world has been led by Art in each country.

2, How is Art today in the Western world ?

Visual art is principal in society, and that’s why it is often used for political propaganda or psychological influence for commerce. This is, so to say, kitsch art. Clement Greenberg once tried to distinguish the avant-garde and kitsch. But now there is no

avant-garde nor kitsch, because the two are mixed and not defined separately anymore(5).

Is This Art? A Guide for the Bewildered is the title of a book of critique of contemporary art (6). The author says that contemporary art has lost the standards for critique. So also that of non-Western countries now has lost the criteria for critique and are confused in this chaotic situation. Everywhere are organized so many exhibitions without common sympathies and criteria, often with colorful commercial publicity. Jean Baudrillard, well known sociologist, said “Le complot de l’art, which means “the conspiracy of art,” but which is, largely, a conspiracy of the art traders (7).

But is Art still alive ?

In the Western world, it is well known that Friedrich Hegel said that not only is it the end of History, but also the end of Art itself. According to his theory, which was that when the Absolute Spirit could no longer be represented in Art, then Art itself belonged to the past. In fact, modernity meant for him the arrival of History, which was the process of Evolution. For him Modern Art came after the end of Art itself. So how can Contemporary Art follow Modern Art ?

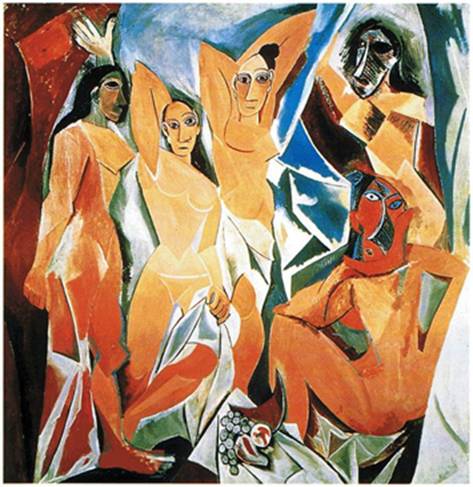

(fig.1)Picasso,Avignon-Ladies,1907.

Anyway, as a matter of fact, it is necessary to distinguish Contemporary Art from Modern Art in the West. Contemporary Art began with Picasso or Kandinsky, and it is not creative but negative to the principles of Western Modern Art that developed in the periods from the Renaissance on, and ended with Impressionism. The theories of the history of art of this creative period in the West had been established by Wolfflin’s style theory(8) or Panofsky’s iconology theory(9). So the theories of the West could be adapted to Eastern Art until the period of Ching (~1912) in China, and of Edo (~1867) in Japan, while since then until the Modern Age, the East made parallel development with Western Art.

Contemporary Art of the 20th century to the present cannot be understood with its theories, in spite of the many explanations of each current, because it is negative and against the theories themselves. The contents of Contemporary Art is the negation and destruction of Modern Art and denies even the understanding of art.

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) was a well-known, typical contemporary artist. He began with Fauvism, but destroyed this style suddenly, and took the way to Dadaism in New York. But then he abandoned painting and represented the “Ready Made.” His “Fountain,” (an upside-down urinal) destroyed all concepts of Art. It’s not a work of Art (10). But this work was chosen as the No.1 work of Contemporary Art in 2004. There are hundreds of the “Fountain” ! The problem of Art now is “How do we create after Duchamp ?”

(fig.2)Duchamp, Fountain. 1917.

Otherwise, when Theodor Adorno (1903-69) wrote the famous phrase, “To write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric”, the creation of art today is considered as a barbaric act for artists. It resembles the phrase, “How do we create after Duchamp ?”

According to Adorno’s theory, Contemporary Art encourages the destruction of traditional art. We understood that not only regional and national cultures, but also classic culture are considered as negative cultures. His theory corresponds well with the idea of multiculturalism today, which denies the traditional culture of each country (11).

As we talked about Contemporary Art, there have not been any outstanding works of art, nor of literature, after World War II. We know the high reputation of Haruki Murakami as a Japanese writer today, but his works clearly have a tendency against the national identity and the tradition of his country. His style of lightness in his novels are received by young generation or by critics who have the tendency to deny traditional culture. But the vacancy in his literary world is favored by them. It is possible to say that the theory of Adorno operated considerably upon the works of Murakami.

The vacancy itself is, ironically, saying that this is the fruit of “barbaric” human beings. Adorno said in this essay, “Cultural Criticism and Society”, that even the understanding of the impossibility of writing a poem has already collapsed. This consideration of the collapse means that the human beings are drowning in the materialization of modern society, according to him.

In this modern world, according to Adorno, the Cultural Industry has dominated society. Frankly speaking, this Industry is mostly directed by Jewish people. Even though they hold a lot of power, they cannot control the people of the whole world.

3.On the case of the Art History of Japan

As already noted, Huntington and Melko separated Japanese from Chinese civilizations and in Asia there are four big ones: Islamic, Indian, Chinese and Japanese. Anyway in the Eastern world, the histories of art of each civilization developed totally differently from the Western histories of art. And the histories of Islam, India and China are relatively well studied by Western scholars, because, for example, in the British Museum there are rather many works of Islamic art, Indian art, and Chinese Art in Western world. But there are not so many works of Japanese art, except of Ukiyo-e, which were so popular in the second half of the 19th century in Europe. Because Japan was not colonized by Western countries, they couldn’t easily bring Japanese treasures to Europe; that also means that the works of art are not so well-studied by foreign scholars. Consequently the study level in foreign countries is not so high in the Western world.

Traditional culture remains always and everywhere in Japan; not only in the museums, but also in the shrines and temples of Shinto and Buddhism. The masterpieces of Buddhist art are conserved not only in Nara and Kyoto, but widespread throughout Japan. Artistic works like scroll paintings or Ukiyo-e paintings are also so numerous. Though it can be rather difficult to understand their meanings, contact with them enables us to communicate with their historical and artistic worlds. The War in the 20th century destroyed many cultural treasures, but the remaining heritage nevertheless is able to connect us to the traditional world to help artists create the art of the future.

My book, The Art History of Japan explains that from Jomon-period art to the present day of Japan, from the point of view of style. The Age of Archaism is the 6-7th century, the Asuka period; the Age of Classicism, the Nara Period, is the 8th century; the Age of Mannerism is from the 9th to the middle of the 12th centuries; and the Baroque Age is the second half of 12th to 13th century. After Baroque Art, in the Muromachi period, 14th through 16th centuries, there is Romanticism to Chinese Landscape (山水画) like Sesshu, and the Kano School. This development of styles is very similar to European Art History(12).

It is very interesting. In fact, Wölffrin’s theory of style was well adapted to The History of Japan. A book review by an Italian scholar said that for Westerners, this book, for the first time, could succeed to make them understand the Art History of Japan, the contents of which are completely different from European Art, but that the development of styles is common (13).

The Histories of Art in Asia were long considered as folk art

or religious art.But we must insist that it is also Art itself. I am preparing to write The History of Chinese Art from this point of view. As we didn’t explain Art History, without learning well the method of studying the art, not only the attributions problems, but also its independent representation from the social background. We always explained the art works according to the expression of the social base. But it is necessary to understand

the artistic contents, which developed in their own style. In

Japan, the art historians described the history of art with the

period of each government. But Art has it’s own stylistic and

iconographic world, which is independent from the social and

political worlds. (14)

.My approach in my book, is to explain the style of Classicism in the Nara period through observations of noble simplicity and quiet greatness of works by Kimimaro, Shogun Manpuku,etc.,who are comparable with the great masters of the European Renaissance. Shomu Tenno (Emperor ) designated Buddhism as the State Religion, alongside indigenous Shinto. In Manyo-shu (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves, a poetry anthology), we can understand the fundamental classical ideas and feelings of the period. In the same way, we could compare the works from the Kamakura period (1185-1333), the era of samurai warriors, with the European Baroque period, Unkei, Tankei, Jokei, etc. were representative of this period.

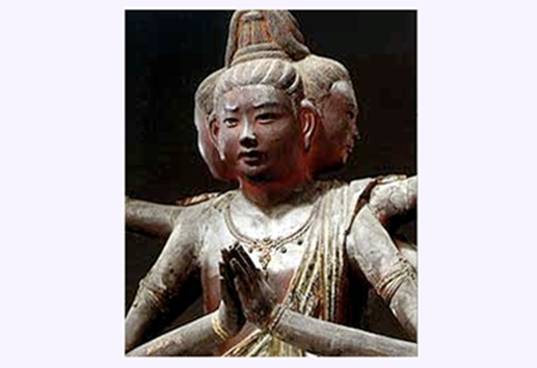

(fig.3)Kimimaro, Nikko,Gakko Bosatsu,Todai-ji temple,Nara

Winckelman, who described the classical style of ancient Greece using phrases like noble simplicity and quiet grandeur (15)—terms that apply equally well to the sculpture of the Nara period. While demonstrating the planar style of which Wolfflin speaks, it demonstrates also the qualities of absolute clarity and plasticity. Examples of this style include the sculptures of the Sangatsudo of Todaiji temple – particularly the pair of bodhisattvas, Nikko and Gakko (fig.3),—the Four Tenno of Kaidan-in, and the Kofukuji sculptures of Eight Bushu (of which the Ashura is justly famous)(fig.4) and Ten Daideshi (Great Disciples of Buddha ). Noble simplicity and quiet grandeur are apt descriptions for these standing images.

What is a common detail of the figures of these sculptures ? For example, the representation of the eyes. In th

(fig.4) Manpuku,Statue of Ashura,Kofukuji-temple,Nara,

e case of Fukuu Kenjaku-Kannnon in the Sangatsu-do Hall in Todaiji in Nara, which is attributed to Kimimaro, Kiminakanomuraji, well known sculptor of the Daibutsu, the Great Statue of Buddha of Todai-ji in Nara. It is a solemn sculptural work, which remains as the work of this great artist. Look at the eyes.

(fig.5)Kimimaro, Fuku-kenjaku-kannon,detail, Todaiji-temple, Nara

(fig.6)Kimimaro, Gakko Bosatsu,detail, Todaiji temple, Nara

The eyes are slanted very slightly upwards, their outline indented a third of the distance from the inside, with a corresponding slight dip in the lower eyelid. If we take this distinctive eye-shape as a stylistic trait of the sculptor responsible for the Daibutsu itself, then surely the same artist was also responsible for the Fuku Kenjaku Kannon in the Sangatsudo Hall of the Todai-ji temple. The images of Nikko and Gakko Bodhisattvas in the Sangatsudo Hall of the Todai-ji temple share this distinctive eye shape. I feel that these two images are among the very best examples of Nara sculpture; the fullness of their faces, their aura of divinity, and the natural quality of their reverent poses elevate them above the merely human even while preserving a feeling of humanity.

The Molerian method of the examination of detail is very useful to attribute to this artist.

This Method was established in the 19th century in Italy for the way of the attribution of individual works of the Italian Renaissance. Now it is almost forgotten as one important discipline, because in Europe, after the development of Museums of Art History from the 19th century, the problems of attribution all were completed, except for a few difficult works.

I proposed in my book, The History of Japanese Art, that we Asian scholars must study the artists in unsigned cases, and try to attribute from the point of view of style. Without the examination of the style, it is not possible to imagine the artist’s own artistic world. The delay of identifying the style and the artists of the ancient period, made the Art Histories in Asia be disregarded in Janson’s famous History of Art, which were ignored almost totally in his survey of world art (16).

Anyway, the Art History of Japan continued until the modern age, the Reform of Meiji (1867~), independently from the History of Western Art. Even Chinese Arts influenced only in the Muromachi period (1333 ~1600) with the current of Landscape Paintings (Sausui-ga). And after the Meiji Era, the influence of Western Art was so strong as to risk the loss of the originality of Japanese art; except for a few artists, like Tessai Tomioka, Tsuguji Foujita, Shiko Munakata who didn’t forget the traditional ways.

![]()

(fig.8)Munakata Shiko,Pleasure, Kanagawa City Hall

In 1986, there was an Exhibition of Japanese Modern Art in Paris; the critiques on the works were rather severe on their imitation of the currents of Western Arts. Because in Japan, there has been no motivation of negativism to traditional Art, like in Europe. Japanese artists could not understand that Contemporary Art began with Picasso, as I analyzed already.

The History of Japanese Painting showed the same story of styles as that of Sculpture. But unfortunately many masterpiece paintings were destroyed, among them the wall paintings in the Kondo at Horyu-ji in Nara, painted at the end of the 7th century, and, sadly, destroyed by fire in 1949. According to photographs, three figures of Buddhas: Shaka, Amida, and Yakushi in Paradise, each shows clearly the Classicism tendency, which are similar to such figures in India, more than those of China, of the same period.

From the Paintings of Buddhism to Ukiyo-e of the 19th century, in which the quality of brush lines is the most important element of their visual expression. The great masters like Toba Sojo, artist of Choju Giga, the picture scroll sometimes called “the first manga,” Sesshu, landscape painter of the 15th century, to Hokusai, famous artist of the Edo period, we appreciate the force of brush lines in their every work.

4.A Conclusion

Finally what is the connection between the past and present in Art ?

Why, for example, could Picasso, Klee, and Munakata be credited as representatives of Contemporary Art? Because, at least, they had vivid lines in their works! The only art that can be appreciated today are works with vivid brush lines, which express the spirits of the artists!

At this point, it makes sense to remind ourselves of the art critique by Hsie Ho (479-?) in his Ku-hua Lu (Evaluating Ancient Paintings 古 画品録), which states “Six Canons” of painting. The first Canon is “Spirit resonance, life energy”(気韻生動) and the second is “Bone structure, technique of the brush(骨 法用筆. Contemporary Art opposes the 3rd to 6th canons, which insisted on the traditional ways of representation. I think the first two Canons are well connected, and these could be the only criteria to value contemporary expressions of art. In this point, the Eastern arts could have the possibility to create a new current of art (17).

Throughout the world, we are in the stage of Contemporary Art and there is no way of escaping from this situation. There are no borders between countries where the Internet dominates. The globalization of the economic world prescribes the same condition to arts. But each country has its own traditions and memories of its people, which could be the basis of creation of new art and new concepts. Considering that point, the role of the Eastern world is more important than ever, because the historical background of its art is less known than that of the Western world.

Frankly speaking, we Asian artists and scholars, who are living outside of Western tradition, must not become deeply involved in the theories and thoughts invented by Westerners. But as this recent idea of economic globalization is diffused in the fields of culture and the arts, so the Western current became influential. The market of art is already international. But even in this condition, we must look for the new idea, which can make Art resuscitate again after Duchamp or Auschwitz.

- In Europe, during the 1920’s, the concept of Euro-centrism appears (e.g. Karl Haushofer, Geopolitik des pazifischen Ozeans) . In the 1970s, Samir Amin in the economic field and Edward Said in the cultural field (Orientalism, 1978). In Japan, already in 1860’s, Yukichi Fukuzawa, criticizing the Eurocentrism, proposed the idea of the conciliation with Japanese culture in Gakumon no susume.( The Recommendation of the Humain Science).

- In the term of Multiculturalism, the meaning of Internationalism is also included, because the inner ethnic problems in the Western countries originated from the emigrants from the minor outside countries. When the ethnic people insist on their own cultures of their countries. Without the study and the mutual understanding of each country, it is not possible to solve the problems. In United States and in Canada, there are so many Asiatic people, included Japanese.

- Friedrich Hegel, The Philosophy of World History, edited and translated by John Sibree, New York: Dover, 1956. (First published 1857.) Lectures on the Philosophy of World History. Volume 1: Manuscripts of the Introduction and the Lectures of 1822–3, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. (Translation of G.W.F. Hegel: Vorlesungen: Ausgewählte Nachschriften und Manuskripte, vol. 12.)

- Arnold Joseph Toynbee (1889 – 1975),A StudyofHistory (1934–1961): Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler ( 1880 – 1936), The Decline of the West (Der Untergang des Abendlandes), 1918 and 1922:

William Hardy McNeill (1917~),A World History, (Oxford University Press, 1967, 4th ed., 1999.: Philipp Bagbee, The Culture and History, 1976.: Samuel P.Huntington (1927 – 2008), The Clash of Civilizations, 1993.: Melko, Matthew,The Nature of Civilizations, 1969. - Clement Greenberg, The Kitsch Style and The Age of Kitsch (1939),in Art and Culture;Critical Essay, Boston-Beacon, 1960.

- Amelia Arenas, Is This Art? A Guide for the Bewildered ,The Exhibition of the same title in Museum Kawamura, in 1998.

- Jean Baudrillard, Le complot de l‘art, illusion et disillusion,Paris,1996.

- Heinrich W ö lflin, Kunstgeschichteriche Grundbegriffe, München, 1915.

- Edwin Panofsky, The Studies of Iconology, 1939; Ikonographie und Ikonologie. Eine Einführung in die Kunst der Renaissance, in: ders., Sinn und Deutung in der bildenden Kunst, Köln, Dumont, 1975.

- Michel Sanouillet, TheWritingsofMarcelDuchamp ,NewYork,1989.

- Theodor W. Adorno, Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft, (“Cultural Criticism and Society”), 1949

- The Art History of Japan ,Japanese edition, Tokyo, 1995 , English edition,Akita International Unoversity Press.2008, Italian editon, Sarda-Accademia di Belle Arti, 2012 .

- Ugenio Barbieri, Hidemichi Tanala, Storia dell’Arte Giapponese, in Parol.Quaderni d’Arte e di Epistemologia, anno XXXIII-no 23,2013.

- On this point, in China and in Korea, if not, it is

necessary to establish in each university the section of Art

History, of which discipline is derived in Europe. - Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1786), History of Ancient Art ,1764.

- Horst Waldemar Janson (1913-1982), History of Art, 1962.

- Hidemichi Tanaka, A comparison of Qi yun sheng dong (気韻生動)Aesthetics with Western Art Theories, in the Acte of The Fourth International Conference on Oriental Aesthetics, Tianjin, 2006.